A BIOGRAPHY OF PRAGUE

“Fidler’s passion and love for the ancient city infuses every word, pours off every page, and if you’ve never been interested in Prague, it will find a way into your heart after reading this book … The times, the places and the people are vibrant, arresting and breathing. The Golden Maze gives us a brilliant living history of Prague, told through stories alive with hundreds of voices chiming in. This is the magic and power of this work.”

“Fidler’s narrative is compelling. He writes in short sections, arching across time, and comparing and contrasting the politics, religion and art of different eras. The entire journey is propelled by the same combination of wide-ranging general knowledge, intellectual rigour and the ease of expression of an experienced journalist.”

“Prague doesn’t let go. This little mother has claws.”

Prague manhole.

In 1989, Richard Fidler was living in London when revolution broke out across Europe. Excited by this galvanising historic, human, moment, he travelled to Prague, where a decrepit police state was being overthrown by crowds of ecstatic citizens. His experience of the Velvet Revolution never let go of him.

Thirty years later Fidler returns to Prague to uncover the glorious and grotesque history of Europe's most instagrammed and uncanny city: a jumble of gothic towers, baroque palaces and zig-zag lanes that has survived plagues, pogroms, Nazi terror and Soviet tanks. Founded in the ninth Century, Prague gave the world the golem, the robot, and the world's biggest statue of Stalin, a behemoth that killed almost everyone who touched it.

Fidler tells the story of the reclusive emperor who brought the world's most brilliant minds to Prague Castle to uncover the occult secrets of the universe. He explores the Black Palace, the wartime headquarters of the Nazi SS, and he meets victims of the communist secret police. Reaching back into Prague's mythic past, he finds the city's founder, the pagan priestess Libussa who prophesised: I see a city whose glory will touch the stars.

*

The legendary founder of Prague was a Bohemian witch-queen named Libussa, who, it was said, stood on a bluff overlooking the Vltava river, stretched out her arms and said: I see a great city … its glory will touch the stars.

Prague is a city of science and imagination, where the nature of planetary motion was decoded, the robot was conceived, and the first science fiction story was written. It’s also a city of magic, where alchemists hoped to create an elixir of eternal youth and to recover the lost language of angels.

*

After the First World War, Prague became the capital of a new independent nation, Czechoslovakia, founded by a philosopher-president. For three decades, the city enjoyed a golden age of culture, democracy and prosperity before falling into the grasp of first Hitler and then Stalin. Prague endured their cruel totalitarian regimes for decades. The darkness of these times was offset by the Praguers’ distinctive form of absurdist humour.

*

Those who come to Prague from new world metropolises like Sydney, Toronto or Los Angeles are sometimes touched by an odd sense of déjà vu, a vague impression of homecoming that can eventually be located in our memories of the old European folktales given to us as children. But Prague’s imaginative landscape is no Disneyland; it’s the natural home of the older, more troubling versions of those tales.

Andre Breton, high priest of the Surrealist movement, was given a hero’s welcome when he came to Prague in 1935. Walking the streets, he instantly grasped that Prague’s surrealist masterpiece was the city itself, a colossal work of automatic writing, scribbled over time from some collective subconscious impulse.

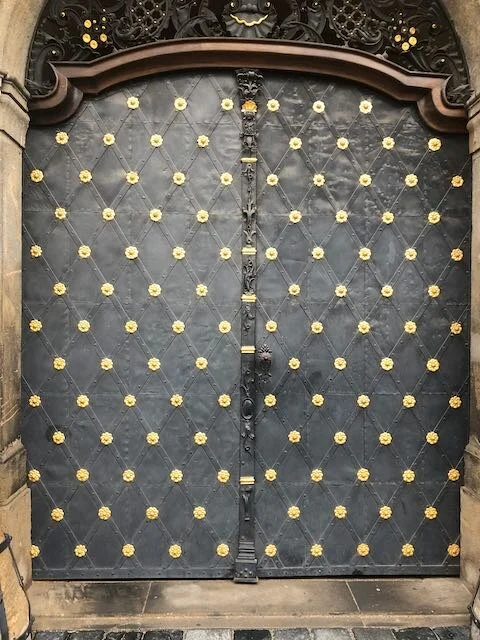

‘Keyholes are glittering in the sky’ wrote Prague’s most lyrical poet Jaroslav Seifert,

and when a cloud covers them

somebody’s hand is on the door-knob

and the eye, which had hoped to see a mystery,

gazes in vain.

– I wouldn’t mind opening that door,

except I don’t know which,

and then I fear what I might find.

The author at Prague Castle in the aftermath of the Velvet Revolution, January 1990 (photo: Josephyne Oliveri).

Europa Regina, with Bohemia and Prague at her heart, from Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographica, 1570.